|

|

Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test Information

Fill out our online form for a P.S.A. testing

inquiry: Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test

Form

- What is the Prostate-Specific

Antigen (PSA) Test?

PSA is a protein produced by the cells of the

prostate gland. The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test measures the level

of PSA in the blood. A blood sample is drawn and the amount of PSA is

measured in a laboratory. When the prostate gland enlarges, PSA levels in

the blood tend to rise. PSA levels can rise due to cancer or benign (not

cancerous) conditions. Because PSA is produced by the body and can be used

to detect disease, it is sometimes called a biological marker or tumor

marker.

As men age, both benign prostate conditions and

prostate cancer become more frequent. The most common benign prostate

conditions are prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate) and benign

prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) (enlargement of the prostate). There is no

evidence that prostatitis or BPH cause cancer, but it is possible for a man

to have one or both of these conditions and to develop prostate cancer as

well.

Although Elevated PSA Advanced Test levels alone do not give doctors enough

information to distinguish between benign prostate conditions and cancer,

the doctor will take the result of this test into account in deciding

whether to check further for signs of prostate cancer.

Back to Top

- Why is the PSA test performed?

As with many other routine

blood tests, PSA is measured from a small sample of blood. Once a blood

sample is taken, the level of PSA in the sample is measured by an accurate

laboratory method called an

immunoassay. The

results are usually reported in ng/ml, shorthand for

nanograms per milliliter.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has

approved the PSA test for use in conjunction with a digital rectal exam (DRE)

to help detect prostate cancer in men age 50 and older. During a DRE, a

doctor inserts a gloved finger into the rectum and feels the prostate gland

through the rectal wall to check for bumps or abnormal areas. Doctors often

use the PSA test and DRE as prostate cancer screening tests in men who have

no symptoms of the disease.

The FDA has also approved the PSA test to monitor

patients with a history of prostate cancer to see if the cancer has come

back (recurred). An elevated PSA level in a patient with a history of

prostate cancer does not always mean the cancer has come back. A man should

discuss an elevated Elevated PSA Advanced Test level with his doctor. The doctor may recommend

repeating the PSA test or performing other tests to check for evidence of

recurrence.

It is important to note that a man who is receiving

hormone therapy for prostate cancer may have a low PSA reading during, or

immediately after, treatment. The low level may not be a true measure of PSA

activity in the patientís body. Patients receiving hormone therapy should

talk with their doctor, who may advise them to wait a few months after

hormone treatment before having a PSA test.

Back to Top

-

For whom might a PSA screening test be recommended? How

often is testing done?

The benefits of screening for prostate cancer are

still being studied. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) is currently

conducting the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening

Trial, or PLCO trial, to determine if certain screening tests reduce the

number of deaths from these cancers. The DRE and PSA are being studied to

determine whether yearly screening to detect prostate cancer will decrease

oneís chance of dying from prostate cancer.

Doctorsí recommendations for screening vary. Some

encourage yearly screening for men over age 50; others recommend against

routine screening; still others counsel men about the risks and benefits on

an individual basis and encourage patients to make personal decisions about

screening.

Several risk factors increase a manís chances of

developing prostate cancer. These factors may be taken into consideration

when a doctor recommends screening. Age is the most common risk factor, with

more than 96 percent of prostate cancer cases occurring in men age 55 and

older. Other risk factors for prostate cancer include family history and

race. Men who have a father or brother with prostate cancer have a greater

chance of developing prostate cancer. African American men have the highest

rate of prostate cancer, while Native American men have the lowest.

Back to Top

- How are PSA results reported?

PSA test results report the level of

PSA detected in the blood. There are several different ways to measure PSA.

Most physicians think that the "normal range" is between 0 and 4.0 nanograms

per milliliter (ng/ml) for the most common PSA tests. (Because some PSA

tests have different normal ranges, you should check with your physician on

this point.) A PSA level of 4 to 10 ng/ml

is considered slightly elevated; levels between 10 and 20 ng/ml are

considered moderately elevated; and anything above that is considered highly

elevated. The lab's "normal" upper level is simply a cutoff point used to

separate men who are less likely to have prostate cancer from those for whom

further prostate cancer testing may be appropriate, depending upon the

circumstances. The higher a manís PSA level, the more likely it is

that cancer is present. But because various factors can cause PSA levels to

fluctuate, one abnormal PSA test does not necessarily

indicate a need for other diagnostic tests. When PSA levels continue to rise

over time, other tests may be indicated.

Back to Top

- What causes PSA to rise?

The level of PSA in the

bloodstream may be elevated by an process that leads to an increase in the

number of cells making PSA or to a breakdown of the normal barriers in the

prostate that prevent much PSA from getting into the bloodstream. The most

common condition leading to a high PSA is benign (noncancerous) enlargement

of the prostate, called benign prostatic hyperplasia

(BPH). BPH is very common in men over the age of 50 and may lead to

difficulty with urination. Infection or inflammation in the prostate, called

prostatitis, may also cause elevation

of PSA by damaging the PSA barrier in the prostate. In

addition, some diagnostic tests, such as a needle

biopsy of the prostate, may increase

PSA levels for several weeks. It does not appear that a routine

digital rectal examination

(DRE) of the prostate by the doctor's finger causes an elevation of the PSA.

Both BPH and prostate cancer

are common in men over the age of 50. In addition, there is a lot of overlap

in blood PSA levels between men with BPH and those with early prostate

cancer. These factors limit the usefulness of PSA as a tool for detecting

curable prostate cancer. Many patients who have a PSA level higher than 4 ng/ml

will eventually be found not to have prostate cancer. These men have a

"false-positive" test. If PSA is tested on men with BPH but no prostate

cancer, as many as one-third to one-half of such men will have an elevated

PSA. Their PSA results, however, are generally in the 4 to 10 ng/ml range.

Back to Top

- What if the test results show an elevated PSA level?

A man should discuss elevated PSA test results with

his doctor. There are many possible reasons for an elevated PSA level,

including prostate cancer, benign prostate enlargement, inflammation,

infection, age, and race. If there are no other indicators that suggest

cancer, the doctor may recommend repeating DRE and PSA tests regularly to

monitor any changes.

If a manís PSA levels have been increasing or if a

suspicious lump is detected in the DRE, the doctor may recommend other

diagnostic tests to determine if there is cancer or another problem in the

prostate. A urine test may be used to detect a urinary tract infection or

blood in the urine. The doctor may recommend imaging tests, such as

ultrasound (a test in which high-frequency sound waves are used to obtain

images of the kidneys and bladder), x-rays, or cystoscopy (a procedure in

which a doctor looks into the urethra and bladder through a thin, lighted

tube). Medicine or surgery may be recommended if the problem is BPH or an

infection.

If cancer is suspected, the only way to tell for sure

is to perform a biopsy. For a biopsy, samples of prostate tissue are removed

and viewed under a microscope to determine if cancer cells are present. The

doctor may use ultrasound to view the prostate during the biopsy, but

ultrasound cannot be used alone to tell if cancer is present.

Back to Top

- What are some of the limitations of the PSA test?

- Detection does not always mean saving lives:

Even though the PSA test can detect small tumors, finding a small tumor

does not necessarily reduce a manís chance of dying from prostate

cancer. PSA testing may identify very slow-growing tumors that are

unlikely to threaten a manís life. Also, PSA testing may not help a man

with a fast-growing or aggressive cancer that has already spread to

other parts of his body before being detected.

- False positive tests: False positive test

results (also called false positives) occur when the PSA level is

elevated, but no cancer is actually present. False positives may lead to

additional medical procedures, with significant financial costs and

anxiety for the patient and his family. Most men with an elevated PSA

test turn out not to have cancer.

False positives occur primarily in men age 50 or

older. In this age group, 15 of every 100 men will have elevated PSA

levels (higher than 4 ng/ml). Of these 15 men, 12 will be false

positives and only three will turn out to have cancer.

- False negative tests: False negative test

results (also called false negatives) occur when the PSA level is in the

normal range even though prostate cancer is actually present. Most

prostate cancers are slow-growing and may exist for decades before they

are large enough to cause symptoms. Subsequent PSA tests may indicate a

problem before the disease progresses significantly.

In addition to false-positive tests, the PSA may be falsely negative -- that is, normal

even when prostate cancer is present. Some 30 to 40 percent of patients with

early-stage prostate cancer have a normal PSA. Repeating PSA tests once

every year may be useful to find some of the cancers in men who have a

normal PSA at first.

False-negative and false-positive

findings limit the value of PSA testing. Despite this, PSA testing has led

to an increase in the detection of prostate cancer.

Back to Top

- Why is the PSA test controversial?

Using the PSA test to screen men for prostate cancer

is controversial because it is not yet known if the process actually saves

lives. Moreover, it is not clear if the benefits of PSA screening outweigh

the risks of follow-up diagnostic tests and cancer treatments.

The procedures used to diagnose prostate cancer may

cause significant side effects, including bleeding and infection. Prostate

cancer treatment often causes incontinence and impotence. For these reasons,

it is important that the benefits and risks of diagnostic procedures and

treatment be taken into account when considering whether to undertake

prostate cancer screening.

Back to Top

- What research is being done to improve the PSA test?

Scientists are researching ways to distinguish

between cancerous and benign conditions, and between slow-growing cancers

and fast-growing, potentially lethal cancers. Some of the methods being

studied are:

- PSA velocity: PSA velocity is based on

changes in PSA levels over time. A sharp rise in the PSA level raises

the suspicion of cancer.

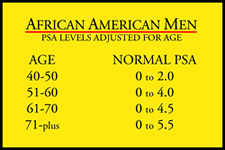

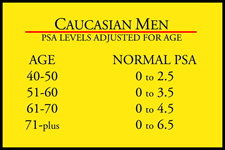

- Age-adjusted PSA: Age is an important

factor in increasing PSA levels. For this reason, some doctors use

age-adjusted PSA levels to determine when diagnostic tests are needed.

When age-adjusted PSA levels are used, a different PSA level is defined

as normal for each 10-year age group. Doctors who use this method

suggest that men younger than age 50 should have a PSA level below 2.5

ng/ml, while a PSA level up to 6.5 ng/ml would be considered normal for

men in their 70s. Doctors do not agree about the accuracy and usefulness

of age-adjusted PSA levels.

- PSA density: PSA density considers the

relationship of the PSA level to the size and weight of the prostate. In

other words, an elevated PSA might not arouse suspicion in a man with a

very enlarged prostate. The use of PSA density to interpret PSA results

is controversial because cancer might be overlooked in a man with an

enlarged prostate.

- Free versus attached PSA:

PSA circulates in the blood in two forms:

free or attached to a protein molecule. With benign prostate conditions,

there is more free PSA, while cancer produces more of the attached form.

Researchers are exploring different ways to measure PSA and to compare

these measurements to determine if cancer is present. In clinical practice, free PSA

serves as an additional tool to help decide which men need more

aggressive evaluation to check for prostate cancer, including a prostate

biopsy, and which men might be safely managed with observation including

serial exams and PSA tests over time. In men presenting with a high

standard total PSA test (certainly any value over 10) or with a

suspicious digital rectal examination of the prostate, there is no

recognized utility for obtaining an additional free PSA test. In most

such cases, prostate biopsy is indicated to rule out cancer. Free PSA

has been proposed as a secondary test in men with a slight elevation or

abnormality of the standard total PSA level, who otherwise have no

suspicion of prostate cancer on their physical exam, and who perhaps

have an enlarged prostate (BPH) which might also cause a mild elevation

of the PSA levels above normal. If the percent free PSA compared to

total PSA is high in such an individual, several preliminary clinical

studies have suggested that it might be safe to avoid a biopsy of the

prostate. This might be particularly beneficial in patients in whom

prostate biopsy is technically difficult, such as those who are on

medical anticoagulation (blood thinners) for a variety of cardiovascular

problems, or the man whose rectum has been surgically removed because of

rectal cancer. It should be emphasized throughout this discussion that

the proper use of free PSA is still a matter of scientific study and

debate. Any man with an abnormally elevated standard PSA test but a

"normal" percent free PSA who chooses, after careful consideration with

his or her physician, to avoid a prostate biopsy, should have careful

medical observation, including repeat PSA tests and prostate exams done

on a regular basis.

- Other screening tests: Scientists are

also developing screening tests for other biological markers, which are

not yet commercially available. These markers may be present in higher

levels in the blood of men with prostate cancer.

Back to Top

|